- Home

- Leonard Gardner

Fat City

Fat City Read online

LEONARD GARDNER was born in Stockton, California. His short stories and articles have appeared in The Paris Review, Esquire, Southwest Review, and Brick, among other magazines. His screen adaptation of Fat City was made into a film by John Huston in 1972; he subsequently worked as a writer for independent film and television. For his work on the series NYPD Blue he twice received a Humanitas Prize (1997 and 1999) as well as a Peabody Award (1998). In 2008 he was the recipient of the A. J. Liebling Award, given by the Boxing Writers Association of America. A former Guggenheim Fellow, he lives in Northern California.

DENIS JOHNSON has published eight novels as well as novellas, short stories, reportage, poetry, and plays. His novel Tree of Smoke won the 2007 National Book Award.

FAT CITY

LEONARD GARDNER

Introduction by

DENIS JOHNSON

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 1969 by Leonard Gardner

Introduction copyright © 1996 by Denis Johnson

All rights reserved.

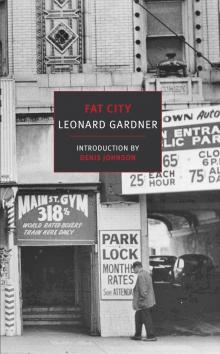

Cover photograph: Marilynn K. Yee, Main Street Gym, Los Angeles, 1976; © 1976 by The Los Angeles Times

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gardner, Leonard.

Fat city/by Leonard Gardner; introduction by Denis Johnson.

1 online resource. — (New York Review Books classics)

Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

ISBN 978-1-59017-893-5 (epub) — ISBN 978-1-59017-892-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-59017-892-8 (alk. paper)

1. Boxers (Sports)—Fiction. 2. Young men—Fiction. 3. Stockton (Calif.)—Fiction. 4. Sports stories. I. Title.

PS3557.A713

813'.54—dc23

2015020741

ISBN 978-1-59017-893-5

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

CONTENTS

Biographical Notes

Title Page

Copyright and More Information

Introduction

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

INTRODUCTION

Exactly which year of the 1960s the book came out, I can’t remember, but I remember well which year of my lifetime it was—I was discovering that it wasn’t a joke anymore, I was actually going to have to become a writer, I was too emotionally crippled for real work, there wasn’t anything else I could do—I was eighteen or nineteen. Newsweek reviewed Fat City, a first novel by Leonard Gardner, in a tone that seemed to drop the usual hype—“It’s good. It really is.” I wanted to get a review like that.

I got the book and read about two Stockton, California, boxers who live far outside the boxing myth and deep in the sorrow and beauty of human life, a book so precisely written and giving such value to its words that I felt I could almost read it with my fingers, like Braille.

The stories of Ernie Munger, a young fighter with frail but nevertheless burning hopes, and Billy Tully, an older pug with bad luck in and out of the ring, parallel one another through the book. Though the two men hardly meet, the tale blends the perspective on them until they seem to chart a single life of missteps and baffled love, Ernie its youth and Tully its future. I wanted to write a book like that.

My neighbor across the road, also a young literary hopeful, felt the same. We talked about every paragraph of Fat City one by one and over and over, the way couples sometimes reminisce about each moment of their falling in love.

And like most youngsters in the throes, I assumed I was among the very few humans who’d ever felt this way. In the next few years, studying at the Writers’ Workshop in Iowa City, I was astonished every time I met a young writer who could quote ecstatically line after line of dialogue from the down-and-out souls of Fat City, the men and women seeking love, a bit of comfort, even glory—but never forgiveness—in the heat and dust of central California. Admirers were everywhere.

My friend across the road saw Gardner in a drugstore in California once, recognized him from his jacket photo. He was looking at a boxing magazine. “Are you Leonard Gardner?” my friend asked. “You must be a writer,” Gardner said, and went back to the magazine. I made him tell the story a thousand times.

Between the ages of nineteen and twenty-five I studied Leonard Gardner’s book so closely that I began to fear I’d never be able to write anything but imitations of it, so I swore it off.

When I was about thirty-four (the same age Gardner was when he published his), my first novel came out. About a year later I borrowed Fat City from the library and read it. I could see immediately that ten years’ exile hadn’t saved me from the influence of its perfection—I’d taught myself to write in Gardner’s style, though not as well. And now, many years later, it’s still true: Leonard Gardner has something to say in every word I write.

—DENIS JOHNSON

FAT CITY

1

He lived in the Hotel Coma—named perhaps for some founder of the town, some California explorer or pioneer, or for some long-deceased Italian immigrant who founded only the hotel itself. Whoever it commemorated, the hotel was a poor monument, and Billy Tully had no intention of staying on. His clean laundry he continued to put back in his suitcase on the dresser, ready to be hurried away to better lodgings. He had lived in five hotels in the year and a half since his wife had left him. From his window he looked out on the stunted skyline of Stockton—a city of eighty thousand surrounded by the sloughs, rivers and fertile fields of the San Joaquin River delta—a view of business buildings, church spires, chimneys, water towers, gas tanks and the low roofs of residences rising among leafless trees between absolutely flat streets. Along the sidewalk under his window, men passed between bars and liquor stores, cafés, secondhand stores and walk-up hotels. Pigeons the color of the street pecked in the gutters, flew between buildings, marched along ledges and cooed on Tully’s sill. His room was high and narrow. Smudges from oily heads darkened the wallpaper between the metal rods of his bed. His shade was tattered, his light bulb dim, and his neighbors all seemed to have lung trouble.

Billy Tully was a fry cook in a Main Street lunchroom. His face, a youthful pink, was lined around the mouth. There was a dent in the middle of his nose. Thin scars lay one above another at the outer edges of his brows. Crew-cut on top and combed back long on the sides, his rust-colored hair was abundant. He was short, deep-chested, compact, neither heavy nor thin nor very muscular, his bones thick, his flesh spare. It was the size of his neck that gave his clothed figure its look of strength. The result of years of exercise, of lifting ten- and twenty-pound weights with a headstrap, it had been developed for a single purpose—to absorb the shock of blows.

Tully had not had a bout since his wife had left him, but last night he had hit a man in the Ofis Inn. What the argument involved he could no longer clearly recall, and he gave it little thought. What concerned him was what had been revealed about himself. He had thrown one punch and the man had dropped. Tully now believed he had given u

p his career too soon. He was still only twenty-nine.

Down stairs carpeted with rubber safety treads, where someone fell nearly every night, he set off for the YMCA to test himself on the punching bags. Enjoying a sense of renewal after a morning of hangover, he walked quickly along the cold streets.

In a subterranean locker room, hearing a din from the swimming pool, Tully removed his clothes. He had four tattoos, obtained while in the army and now utterly disgusting to him: a blue swallow in flight over each nipple, a green snake wound up his left wrist, and on the inside of his right forearm a dagger piercing a rose. Wearing pale-blue trunks and a gray T-shirt, he went silently down a corridor on soft leather soles toward the sound of a furiously punched bag. When Tully entered the room at the end of the corridor, a tall, lean, sweating youth glanced up, took a final swing at the bag and sat down on a bench amid a disarray of barbells on the cracked concrete floor. There was no one else in the room. Tully swung his arms, rolled his neck, squatted, and rose in alarm at a loud pop in his knee, conscious all the while of the boy’s stillness. After his violent activity at the bag, he now sat motionless on the bench, looking at the wall. It was the attitude of one wishing to repel attention, and so, perversely, Tully invited him to box, though he himself had come here only to punch the bag.

The boy rose then, quickly and gloomily. “You a pro?”

Tully could see he was looking at his brows. “I was. I’m all out of shape now. We’ll just fool around easy, and I can show you a few things, okay? I won’t hit you hard.”

His face morose, the boy went off to check out the gloves. Tully continued his warm-up and was breathing heavily by the time the other returned. They pulled on the gloves in silence and entered the ring. When Tully reached out to touch gloves, the boy sprang warily away. Smiling tolerantly, Tully pursued him. After that he felt only desperation because everything happened so quickly: smashes on his nose, jolts against his mouth and eyes, the long body eluding him, bounding unbelievably about the ring while Tully, flinching and covering, tried to set himself to counter. In sudden rage he lunged, swinging like a street fighter, and his leg buckled. Hissing with pain, he began hopping around the ring.

That was how it ended. Bent over, kneading a pulled calf muscle, his face contorted, Tully asked between clenched teeth: “What’s your name, anyway?”

The boy remained at the far side of the ring. “Ernie Munger.”

“How many bouts you had?”

“None.”

“You’re shitting me. How old are you?”

“Eighteen.”

Tully gingerly took a step. “Well, you got it, kid. I fought Fermin Soto, I know what I’m talking about. I mean nobody used to hit me. They couldn’t hit me. They’d punch, I wouldn’t be there. You ought to start fighting.”

“I don’t know. I just come down to mess around. Get a little exercise.”

“Don’t waste your good years. You ought to go over to the Lido Gym and see my manager.”

In the showers, Tully was thankful he had not gone to the Lido Gym himself. Beside him water streamed over Ernie Munger’s head. The boy’s shoulders were broad, his chest flat and hairless, his waist narrow, his arms and legs long and slender, and looking at his face, Tully regretted that he had not had a chance to hit it squarely. It was well formed and callow, the forehead wide and high, the nose prominent. In the dressing room with a towel around his waist, Tully brought a pint of Thunderbird from his athletic bag, and sensitive to its impropriety here in the YMCA, he took a drink with the metal door of his locker blocking him from Ernie’s view. In the ceiling a ventilator labored in vain against the odors of sweat and soap and musty athletic clothes.

Tully limped upstairs and, whispering curses at his leg, started back toward his hotel. The sun was setting on a gray day, tinting mauve the flat undersides of clouds beyond the deserted shipyard where two great cranes slanted against the sky. Leaves and papers blew along the gutters. Boats rocked in the floating sheds of the yacht harbor. Farther down the channel a lone freighter was moored by a silo fifty miles from the sea.

There were few figures along Center Street. In the Harbor Inn half the stools were empty. Tully seated himself with care, grasping the edge of the bar. Opposite the notice

PLEASE DON’T SPIT

ON THE FLOOR

GET UP AND SPIT

IN THE TOILET BOWL

I thank you

he ate a pickled pig’s foot on a napkin and drank a glass of port. He was eating a bag of pork cracklings when a familiar couple sat beside him. The man was a Negro, with a parted mustache and bald temples, his face indolent and dejected. The woman was white, near Tully’s age, with thin pencil lines where her eyebrows had been and a broken nose much like his own.

“Don’t you ever go home?” she asked him.

“I just got here.”

She turned to her companion. “What’s keeping him? He knows we’re here. Can’t you make him come over and serve us?”

“Just take it easy. He be here.”

“Well, you spineless son-of-a-bitch, you’d take up for anybody against me.” She stared ahead, face propped in both hands. “I want a cream sherry.” Then she was again speaking to Tully. “Earl and I have something very wonderful together. I love that man more than any man’s got a right to be loved. I couldn’t live without him. If he left me I just couldn’t make it. But you think he’d even raise his voice to get me a drink? No. He’ll just sit there and let him ignore us.”

“Here he come,” said Earl.

“No thanks to you.”

Tully shifted his leg, wincing. He gave a small groan and the woman glanced at him. “Charley horse,” he said. When she did not inquire, he went on to tell what had happened to him just as he had been about to get into shape.

She spoke over her shoulder. “Earl?”

“Uh huh.”

“This guy’s a fighter.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Christ. Why did I even mention it? What do you know about it anyway?”

“Not much.”

“That’s what I mean. Sorry to bother you. Why did I open my mouth? I apologize. Well, what do you want? I said I was sorry, what more can I say?”

Earl gazed toward the mirror, where a row of gloomy faces looked out into the room. “I hear you, baby.”

“You sure don’t act like it.” With a sigh she took up her glass. “Sometimes I wonder why I put up with him. Basically they’re a mistrustful people. You don’t know the things I do for that man, but he couldn’t care less. You’re not as black as he is, then you’re shit in his book. He don’t like me talking to you, I know. I got to talk to somebody.”

“This kid could make a lot of money some day,” Tully continued. “He’s a natural athlete.”

“What’s his name?” Earl inquired, leaning in front of the woman, his face impassive.

“You wouldn’t know who he was if he did tell you.”

“Just asking.”

“Got to know everything. Now he won’t talk. He’s mad. Butts in and then shuts up. I wanted to hear this.”

“There’s nothing more to hear. That’s it. The kid’s a natural, that’s all. They come along about one in a million.” Enjoying himself, Tully signaled for another drink.

“He’s so goddamn sour. I’m having a good talk, that’s what’s eating him. I don’t see why I can’t have a little fun. Let him sit there and stew, I don’t care. If that’s what he wants, why should I? I believe everybody’s got a right to live his own life. So screw everybody.” She straightened, her voice louder. “I want to say something. I want to give a toast to this gentleman. I’ll make it short, just a few words. Here’s to your health. God bless you and keep you in all your battles.”

Not a head turned as she raised her glass. With large, dark, intense eyes she regarded Tully until he too, in embarrassment and sudden erotic curiosity, lifted his drink.

“Oma?”

“What is it?”

“

Nothing.”

She turned. “For Christ’s sake, what do you want then? Can’t I even talk to anybody?”

“I’m not stopping you.”

“No, you’re not stopping me. Oh, no, you just sit there with your sad-ass face shut until the minute I start having a good time. I’m sick of your bellyaching. Is it my fault if you can’t fit in? Why can’t you mind your own business? And that goes for the rest of you. None of you is worth a fart in a windstorm. So to hell with it.” She got down from her stool and went off toward the back of the room.

Uncomfortable, Tully studied the cigarette-burned surface of the bar. A glass of port was set down by his hand. “Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it,” said Earl. “I don’t claim to be nothing more than I am. You maybe can fight, I’m an upholsterer.”

“That’s the way it goes.”

“One man got muscles, another got steel. It all come out the same.”

They drank in silence. When the woman returned, Tully rose and went out. He crossed the dark street to his hotel and limped up the stairs. On the bed in the dim light, hearing coughing from across the hall, he knew he had magnified Ernie Munger’s talents. He had done it in order to go on believing in his body, but he had lost his reflexes—that was all there was to it—and he felt his life was coming to a close. At one time he had believed the nineteen-fifties would bring him to greatness. Now they were almost at an end and he was through. He turned onto his side. On the worn linoleum lay a True Confession and a Modern Screen, magazines he once would not have thought could interest him, but in reading of seduction and betrayal, adultery, divorce and the sorrows of stars, he found the sad sentiment of his love.

Tully had met his wife at Newby’s Drive-Inn, a squat white building covered with black polka dots in the center of an expanse of asphalt shaded by mulberry trees. Despite the staining berries that had dropped on his yellow Buick convertible, he had gone there to see her every night. A carhop in tight black slacks and white blouse, she had presented a spectacular image. He could not stop thinking of her. Expensively dressed and winning fights, he felt he had to have her, and he was a proud husband, especially when she accompanied him to the local bouts, on the nights when he went as a spectator. Entering the auditorium on his arm, wearing knitted wool jersey—orange or white—or low-cut dresses held up by minuscule straps, in high backless shoes and with her long auburn hair piled on her head, she had roused the gallery to tumultuous shouting and whistling. He had come to expect it, walking in carrying her coat. That period had been the peak of his life, though he had not realized it then. It had gone by without time for reflection, ending while he was still thinking things were going to get better. He had not realized the ability and local fame he had then was all he was going to have. Nor had his manager realized it when he moved him up to opponents of national importance. That knowledge had been mercilessly pounded into Tully in a half dozen bouts as he swung and missed and staggered, eyes closed to slits. Then he had looked to his wife for some indefinable endorsement, some solicitous comprehension of the pain and sacrifice he felt he endured for her sake, some always withheld recognition of the rites of virility. Waiting, he drank. After six months he fought once more and was knocked out by a man of no importance at all. Then he began to wish for someone who could give him back that newly-wed wholeness and ease, but it was a feeling he could not find again, and he knew now that his mistake had been in thinking he could. That was how he had lost her—by looking for it. Without her he could not get up in the morning. He lost his job at the box factory and found another driving a truck. After he lost that too, the truck on its side in a ditch along with a hundred lugs of apricots, he lost his car. Now he brought an occasional woman to his room, but none of them could give him anything of his wife, and so he resented them all.

Fat City

Fat City